What is MDT (Mechanical Diagnosis & Therapy)?

A Clinical Reasoning Process and an Effective Treatment Method.

MDT (Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy), also known as the McKenzie Method, is a reliable, internationally standardized assessment system that allows therapists to determine the kind of problem with which a patient is presenting, and streamline the most effective treatment for it. It is the most researched assessment system and can be applied to all musculoskeletal conditions.

The aim is to divide the patients into categories, because the treatment is different for each category. In short, we can usually classify conditions into one of three categories:

- Can improve rapidly (with a very precise and specific exercise)

- Can improve slowly (with other types of exercises)

- Physio will not help (requires medical assistance: for imaging, injections, etc.)

Determining the nature and underlying cause of the condition is important as the entire clinical course of care depends on it. For example, one doesn’t want to have surgery for a problem that could have been quickly resolved with exercises. Similarly, nobody wants to be wasting time doing exercises when what is actually needed is an injection or surgery. So a thorough yet efficient assessment is paramount.

Let’s take low back pain as an example. Not all back pain is the same, just like not all chest pain is the same. Since there can be different sources of chest pain (heart, lungs, esophagus, muscles, ribs, etc.) the treatment would be very different for each category. This is exactly the same for low back pain. Before one starts treating pain with different types of interventions all mixed together, one should first find out in which category the condition is.

The mechanical therapists at Expertise Physio are highly trained to use this type of advanced clinical reasoning process when evaluating a musculoskeletal issue. They will guide you through the process of properly classifying your problem in order to then treat it appropriately and thus more effectively.

Where is the source of the problem?

The location of pain may not indicate where the problem is coming from.

Does this surprise you? It may be counterintuitive, but this phenomenon is common and in medicine it is called “referred pain”. Referred pain is simply pain that is felt somewhere else from the actual source. The most familiar occurence of this would be pain felt in the left arm when someone suffers a heart attack. The problem is obviously not the arm, but patients will often complain of pain in that area during an episode of angina.

This happens because the nerves that allow you to feel your heart converge with nerves that allow you to feel your left arm, as they make their way to your brain. Therefore, the brain can get confused as to where the symptoms are coming from and mistakenly produce arm pain in addition to chest pain. As amazing as our bodies are, they are not perfect and “errors” like this can happen. For a longer, more in-depth explanation please consult the attached article.

So how is referred pain relevant to physiotherapy?

There are many cases where the pain generator lies further away from the pain site. Sciatica (leg pain that is coming from the lower back) is a good example of this. It would be ineffective to treat the leg in the case of sciatica, just as it would be ineffective to treat the arm in case of a heart attack.

There are less obvious cases as well. At Expertise Physio, we often see isolated hip pain, knee or ankle pain that can rapidly disappear with lower back exercises. It is also common for local shoulder pain, elbow or wrist pain to be referred from the neck. Considering this information, it would be a costly mistake to focus your time and energy on the arm or leg if it was actually the spine that was responsible for the symptoms that you are experiencing. So if you are dealing with pain or any odd sensations (cramps, tingling, numbness, etc.), give us a call and we will help you sort out where the symptoms are coming from and what you need to do to improve them.

Article:

Menon A, May S, “Shoulder pain: Differential diagnosis with Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy extremity assessment – A case report”. Manual Therapy Journal (2013) 18:354-357.

Article:

Murray GM. (MDS, PhD) “Referred Pain.” Journal of Applied Oral Science (2009) 17.6:i. PMC. Web. 25 July 2018.

Article:

Pheasant S. (PT, PhD), “Cervical contribution to functional shoulder impingement: two case reports.” International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy (2016) Dec;11(6):980-991.

Imaging findings can be misleading.

Images tell the truth, but not the whole story.

X-Rays, MRIs, and CT scans are frequently prescribed in order to better diagnose and treat musculoskeletal issues such as low back pain, neck pain, shoulder or knee pain. However, is has been frequently shown that imaging findings often lack clinical correlation. In fact, multiple studies have shown that many adults have positive imaging findings (abnormalities) however report having absolutely no pain in the area of the imaging finding. In the lumbar spine, a majority of adults have one of the following issues without having any symptoms: disc bulges or herniations, degenerative discs, facet arthropathy and other issues (1). This has lead to strong recommendations against the use of routine MRIs for chronic low back pain (2). For most people with simple low back pain, an anatomic diagnosis is not possible, and is actually considered unnecessary (3).

As for the neck, one study showed that about 88% of healthy adults have some degenerative discs in their neck, without having any pain whatsoever (4). The shoulder is similar, in that 15% of adults have a full-thickness rotator cuff tear, and 20% have a partial thickness tear, without there being any pain or noticeable weakness. For those over 60 years of age, more than 50% have an asymptomatic rotator cuff tear (5). The knee is no different: it has been shown that osteoarthritis seen on x-rays is not correlated with actual knee pain or disability (6), and that meniscal and cartilage tears of the knee can be asymptomatic even among professional athletes (7).

Think of the example when your car is making a noise or not running well. If you open the hood of the car, take a picture, and provide your car mechanic just with that picture, the image alone will not be enough to fully understand the problem. He might need to take it for a test drive, move it, or run some diagnostic tests. By conducting a proper mechanical evaluation he will get much more information on the problem than just looking at a picture.

What does this mean for physiotherapy? We must do a thorough clinical exam that assesses changes in symptoms and mobility in response to movement-based testing. Only through this type of mechanical assessment can one determine correlation or lack thereof between imaging findings and clinical findings.

Article 1:

Jensen MC, et al. “Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain”. The New England Journal of Medicine. (1994), 331 (2): 69-73.

Article 2:

Chou D, et al. “Degenerative Magnetic Resonance Imaging Changes in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review”. Spine. (2011) 36 Suppl 21S: S43-S53.

Article 3:

Jarvik JG. “Imaging of adults with low back pain in the primary care setting”. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. (2003), 13 (2): 293-305.

Article 4:

Okada E. et al. “Disc degeneration of cervical spine on MRI in patients with lumbar disc herniation: comparison study with asymptomatic volunteers”. European Spine Journal. (2011), 20 (4): 585-591.

Article 5:

Sher JS, et al. “Abnormal Findings on Magnetic Resonance Images of Asymptomatic Shoulders”. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-American Volume. (1995), 77(1):10-15.

Article 6:

Bedson J, Croft PR. “The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic search and summary of the literature”. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. (2008), 9:116.

Article 7:

Kaplan LD, et al. “Magnetic resonance imaging of the knee in asymptomatic professional basketball players”. Arthroscopy: Official Publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. (2005), 21(5): 557-61.

What is Mechanical Pain?

The majority of musculoskeletal problems are mechanical in nature.

Mechanical pain is very common and can originate from any articulation of the body (neck, back, shoulder, knee, wrist, etc). If the pain comes and goes, it is usually mechanical. It often produces discomfort that can be felt at the location of the problem, but sometimes radiates further. In addition, this pain can be negatively or positively affected by movements and positions.

According to the studies below, about 67% of low back pain and 90% of neck pain is mechanical in nature. In the arms and legs (which include shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, knees, ankles, etc), up to 43% of problems are of mechanical origin, depending on the body part.

The interesting particularity of mechanical pain is that it can be made quickly better when the right movement is performed. Despite how long the symptoms have been present and despite the different forms of treatment you have tried in the past, it is possible that no one has yet exposed this rapidly reversible condition that you may have.

Of course, as common as it is, not everyone has mechanical pain. The challenge is thus to determine if your condition is mechanical or not. At Expertise Physio, we are accustomed to seeking out mechanical pain and treating it accordingly. To do so, we start by asking you specific questions in order to get an understanding of the problem. A physical examination then follows, during which we will be monitoring how your symptoms respond to certain movements and positions. Most of the time, on the very first day we get a good understanding of how the problem behaves and what kind of movement-based home program is required to fix it. In this way, we emphasize self-treatment and attempt to minimize the total number of sessions needed.

For more information on Mechanical Pain, see the video “Understanding Back Pain & Sciatica“.

Article:

May S, Aina A. “Centralization and directional preference: a systematic review.” Manual Therapy, (2012), 17(6):497-506.

Article:

May S, Rosedale R, “A survey of the McKenzie classification system in the extremities: prevalence of the mechanical syndromes and preferred loading strategy.” Physical Therapy (2012), 92:1175-1186.

Article:

Werneke MW, et al. “Prevalence of classification methods for patients with lumbar impairments using the McKenzie syndromes, pain pattern, manipulation and stabilization clinical prediction rules.” J Man Manip Ther (2010), 18:197-210.

Rapidly Reversible Low Back Pain:

An important paradigm shift in medicine.

In this seminal 2008 article, a summary of research is presented regarding management of low back pain, and it is emphatically stated that most cases of low back pain are in fact rapidly reversible. What this means is that within days, a person can feel and function significantly better, usually by regularly performing one specific, personalized exercise that has been determined to be beneficial for that person. This is true even for those who have had their pain longer than 3 months, as well as those with sciatica (nerve root compression).

This is an important paradigm shift, as the article argues that many assessment and intervention techniques are ineffective, and that the primary intervention required for most people can be a simple exercise along with posture modification. The exact nature of this exercise is determined during a mechanical assessment, based on the person’s response to performing that movement.

The notions above are at the core of mechanical therapy, which is practiced at Expertise Physio, and can be transposed to all joints in the human body.

Article:

Donelson R. (MD, MS) “Is your client’s back pain ‘rapidly reversible’? Improving low back care at its foundation”. Professional Case Management. (2008), 13(2).

Article:

Wetzel FT. (MD), Donelson, R. (MD, MS) The role of repeated end-range/pain response assessment in the management of symptomatic lumbar discs.” The Spine Journal (2003) 146–154.

Does it matter which exercise?

Some exercises can help your back pain, others can make it worse.

If there is one thing that we know from the literature published over the last few decades, people with low back pain do better if they remain active and exercise, rather than rest and be sedentary.

Does that mean that all kinds exercises should be performed to help with low back pain, and that they are all equivalent? Of course not, especially if you have what we call “mechanical low back pain”. For more information about what Mechanical pain is, please click here: —–

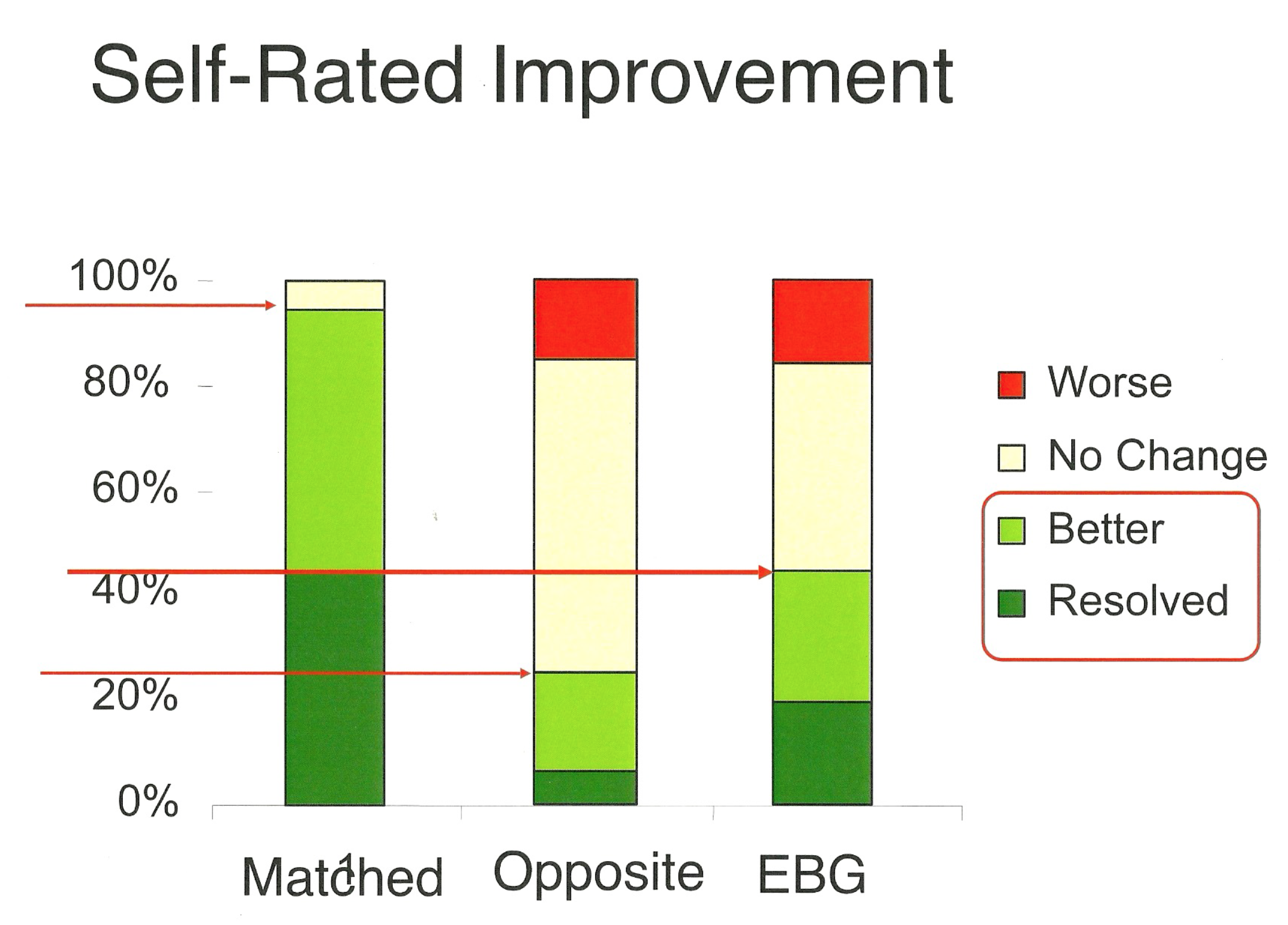

The study clearly demonstrates that doing the right exercise can make all the difference. Here is what the authors did: 312 participants were screened, and 74% of them had mechanical low back pain, meaning that they could get better when they exercised in one specific direction, which could vary from one person to the next. In other words, some people had to do forward bending exercises to get better, some had to do backward bending exercises, and others had to do side-bending/rotation exercises.

When the physiotherapists gave the patients anything else than the direction that was needed to reduce their symptoms, 65% of the participants either got worse or did not improve. On the other hand, when the physiotherapist matched the correct exercise with the appropriate patient, 94% of the participants improved significantly and none got worse.

This explains why there are no panacea exercises that help absolutely everyone with low back pain. Some will say they feel better with swimming, whereas other say they get worse. The same is true with yoga, with walking, with lifting weights, etc. Everyone responds differently to movement, and therefore must receive personalized exercises.

So how can you tell which exercise is good for you? That is where a thorough evaluation from one of our therapists can help. Consult us to see if your back problem can be rapidly reversible. If it is, we will make sure you get the exercise that is right for you.

Article:

Long A, et al. “Does it matter which exercise? A randomized control trial of exercises for low back pain”. The Spine Journal (2004), 29(23):2593-2602.

Knee Osteoarthritis:

Arthritis is not necessarily the cause of your knee pain.

In fact, about 40% of all knee problems can be rapidly reversible, even if you have osteoarthritis. You may ask: “How is that possible? I have seen it on my Xray!” Well, you’d be surprised, as the Xray may tell you the truth but not the whole truth. For more on the topic of imaging, please refer to (link to our “imaging” post).

In this recent 2014 study, exercises were given to 180 patients who were expecting to have a total knee replacement. Needless to say, to be put on a waiting list for surgery meant that these patients had moderate to severe osteoarthritis. However, despite that fact, significant improvements with pain and function were seen as early as 2 weeks after starting the treatment and remained significant 3 months later. And although the exercises were painful to perform, not one person got truly worse. In addition, 40% of these patients were found to have symptoms that could be rapidly reversed with a simple exercise and could delay or even avoid the surgery altogether!

Take home message:

If you have osteoarthritis, you have to keep moving! Exercise in general is good for the knees. However, some people need a variety of different movements, while others need a single, specific movement.

So if your knees are bothering you, consider a consultation at Expertise Physio. You may find that your knee problems are not due to “overuse” or “age” or ‘‘alignment” as you may have been lead to believe.

Article:

Rosedale R, et al. “Efficacy of exercise intervention as determined by the McKenzie System of Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial.” Journal of Orthop & Sports Phys Therapy. (2014) Mar;44(3):173-81